Liberties says its analysis, using data from 37 rights groups in 19 countries, shows the EU needs to act faster against clear rule-of-law backsliding to prevent another Hungary happening.

The Civil Liberties Union for Europe, also known as Liberties, said in its annual report published on Monday that the rule of law in EU member states continued to deteriorate in 2023, as governments across the region further weakened legal and democratic checks and balances.

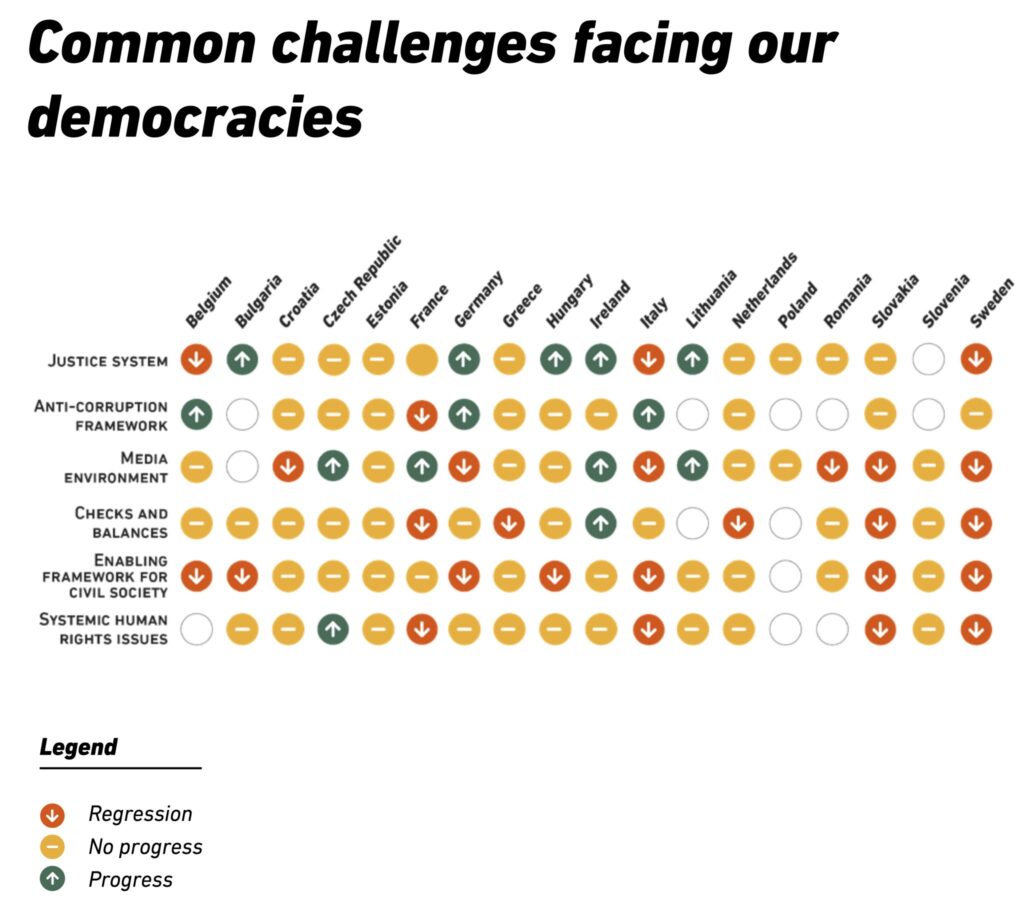

Liberties’ “Rule Of Law Report 2024” – a collaboration of 37 human rights organisations covering 19 EU countries, which the European Commission takes into account when it compiles its own annual report on the state of the rule of law in the bloc during the summer – found the pattern of the deterioration in the rule of law fell into several groups.

In older democracies with mainstream parties in government (France, Germany, Belgium), the challenges to the rule of law remained sporadic. In other long-established – so more resilient – democracies where far-right parties are in power or influencing power (Italy, Sweden) the deterioration risks becoming systemic. And in those countries that are less resistant to rule of law backsliding, such as Greece, infringements of European standards add up and constitute a negative trend in certain fields.

In less-resilient emerging EU democracies, the rule of law trajectory “can swing rapidly – either towards recovery or decline”, it said.

Case in point is Slovakia, where the recently formed government of Robert Fico, inspired by Hungary’s model, is systematically dismantling democratic structures via changes to the criminal code and actions against the independent media. Meanwhile, in Slovenia, the new pro-democratic administration is actively working to mend the situation, while Poland’s experience “highlights the intricate challenge of restoring the rule of law without inadvertently breaking the very legal foundations one seeks to revive”, the report noted.

The emerging democracies feature highly in the report’s key findings concerning: politicised, under-funded and unfair justice systems (Bulgaria, Slovakia); half-hearted efforts to tackle corruption (Hungary, Czechia, Romania); media freedom and pluralism in peril (Croatia, Czechia, Slovakia, Slovenia); insufficient legal and democratic control over the political branches (Hungary, Bulgaria, Croatia); authorities stifling civil society and the voice of the people (Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary); and marginalised groups either neglected or actively attacked for political gain (Slovenia, Croatia).

Liberties noted that the EU has had a long time to process the shock caused by the rise of the illiberal regimes in Hungary and Poland, and EU institutions have spent many years developing their rule of law toolbox. “As a result, the EU is better equipped than ever before to successfully tackle rule of law back-sliding,” it said.

However, it also said its analysis showed the need for the EU to act faster against clear rule-of-law backsliding.

“Liberties’ Rule of Law Report 2024 shows that intentional harm or neglect to fix breaches to the rule of law by governments, if left unaddressed, can evolve into systemic issues over time,” said Balazs Denes, executive director of Liberties. “The growing far right, building on these abuses, will very quickly dismantle European democracy if the European Commission does not use the tools at its disposal, including infringement proceedings or conditional freezing of EU funds, much more assertively.”

Hungary underscores the limitations of relying solely on EU pressure and sanctions for reform, where a real shift necessitates ongoing support for democracy at the grassroots level, as institutional capture remains a persistent obstacle to genuine change. “There is no need to wait until a captive state like Hungary’s emerges with an irremovable anti-democratic regime,” he added.