A damning draft audit into the workings of the Bank of Albania – declared secret but obtained by BIRN – found the central bank printed money to fund the purchase of an iconic Tirana hotel and other expenditures.

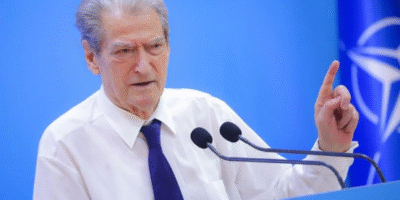

In 2010, Albania’s prime minister at the time, Sali Berisha, surprised many when he announced the sale of Tirana’s iconic Hotel Dajti, built in the 1940s under Italian occupation and used to spy on foreign visitors under communism.

By then, the hotel had been closed for a decade. The surprise was caused not so much by the sale, but by the buyer – Albania’s central bank.

The opposition at the time, the Socialist Party, cried foul, pointing out that the bank, which agreed to pay 30 million euros for the building as new office space, is banned by law from financing government expenditure. But the then bank governor, Ardian Fullani, dismissed the complaints; the renovation went on for years, at a cost of some 18 million euros.

The Socialists had forgotten their complaints when the inauguration of the bank’s new offices came round in May 2023, by which time the party had been in power for a decade. Prime Minister Edi Rama said the renovation had restored “an important monument to the cultural identity of the country”.

A less glowing tribute, however, had come six years earlier in the form of a confidential draft report by Albania’s Supreme State Audit, recently obtained by BIRN. The final version remains under wraps but BIRN was briefed on its contents by sources close to the Supreme State Audit.

The Audit found that the central bank had used monetary issuance to fund the purchase and renovation of the building – i.e. it had printed money, a move that can fuel inflation and thus ultimately pass the cost onto consumers.

“At the moment that a decision is taken to print money, that inevitably causes inflation and these expenses have been ultimately paid by consumers through higher prices,” said Pano Soko, an economics expert and leader of the small opposition party Nisma Thurrje.

And that was not all.

The draft report detailed spending by the central bank well in excess of its earnings and raised concerns about an office rental contract it signed with a local company and respect for procurement procedures during the purchase of several cars.

In a response for this story, the Bank of Albania denied printing money to finance its own expenses and said the audit’s finding were preliminary and eventually adjusted.

Bank denies wrongdoing

Concern has been growing for some time over the central bank’s ledger, which slipped into the red over the past two years.

The draft audit seen by BIRN covers the period when Fullani was governor – 2004-2014 – and the reign of current governor Gent Sejko.

While the authors of the draft said the practice of printing money to finance expenditures began under Fullani, they said it continued under Sejko, and also questioned the procedures followed under Sejko for the purchase of a luxury Range Rover for the bank. Sources told BIRN that the findings concerning the Range Rover were dropped from the final report.

Asked for comment, the Bank of Albania said the 2017 findings cited by BIRN were only preliminary and were later corrected.

“There has been no [final] finding or recommendation from the KLSH,” the bank said, using the Albanian-language acronym for the Supreme State Audit. “It was just some parts of the preliminary report which, as the process foresees, was revised by the auditors following the presentation of the documents and the relevant legal framework by the audited party.”

“The money issuance, as it is foreseen in the law, is carried out for the purpose of fulfilling the needs of the country’s economy for money. Money issuance has never been used for the purpose of paying the expenses of this institution.”

Former governor Fullani did not respond to requests for comment. Bujar Leskaj, the former chairman of the Supreme State Audit and currently an opposition MP, defended his decision to declare the audit report confidential, citing “the specifics of the audited body and the sensitivity of the issues covered”.

Spending beyond its meansAlbanian law requires that the central bank cover its expenses with the money it earns from lending activity and other services, not by printing money. It also says that the bank should keep 25 per cent of its net profits as a reserve and transfer the rest to the state budget.

Over the past decade, however, the bank has become a byword for politically-motivated hiring, particularly from among relatives of the politicians in power. The recruitment drive has eaten into bank profits.

Between 2007 and 2010, the bank transferred some 181 million euros of its profits to the state budget but kept nothing aside for possible capital investments.

In their preliminary report, the auditors concluded that, when the 30-million purchase of the Hotel Dajti was announced, the bank did not have the money to pay for it.

“The reserves for capital investments in 2010 were lower than the current expenses,” the draft report states. “As such, it is clear that the capital expenditures of the Bank of Albania for the period between 2010 and 2014 have been covered through monetary issuance.” Sources told BIRN that this element remained in the final report.

Eduart Gjokutaj, a financial expert and head of the Tirana-based consultancy Altax, said money issuance is only conducted to meet an economic need for the currency.

Printing money to finance a single transaction “clearly goes against the strategy of the central bank and also damages its integrity by putting the needs of the government ahead of those of the national economy”.

At the time of the purchase, Socialist Party MP Erjon Brace, then in opposition, said it was clear that the Bank of Albania was “providing money for the government’s empty account”.

According to the auditors, however, the practice did not stop with the Dajti.

“Based on the information presented, the KLSH observes that the value of physical assets in the Bank of Albania financial statements has grown faster than the reserve,” they wrote. A net increase of some 700 million leks, or seven million euros, “cannot be explained by the reserves and, as such, has been financed via monetary issuance”. Again, sources said this remained in the final report.

Gjokutaj told BIRN the impact on the general level of prices was limited, but added: “Since new money was injected into the economy without a specific or periodic analysis, without transparency or accountability, it created a change in the quantity of the local currency in circulation.”

Soko, the economics expert and opposition politician, said the Bank of Albania’s Supervisory Council should be held to account.

“Surely the justification for such activity and any decision related to it deserves to be investigated,” he said.

The auditors also questioned the price the bank paid for the hotel, saying it was likely inflated.

In 2015, the bank carried out its own evaluation of the asset and concluded it was worth 2.4 billion leks, roughly 24 million euros – not the 30 million that the bank paid for the hotel before investing another 18 million to renovate it.

Rent paid to personal account

As the renovation was going on, the Bank of Albania rented offices in a building owned by property developer and Tirana Sports Club president Refik Halili, via his company Halili shpk.

At the time, however, the auditors said that Halili shpk was in debt to the Albanian tax office due to unpaid social insurance. By 2016, the company’s bank accounts were frozen, so the Bank of Albania paid the rent for the offices to the personal account of Halili’s wife, Xhakonda, who was employed as the administrator of Halili shpk.

“The law and regulations on tax procedures are clear that payments must be carried through company bank accounts, in this case, that of Halili shpk, and not the personal accounts of administrators,” the report states.

The auditors said that the procurement rules drafted by the bank commission for the rental of office space “raise doubts that this company [Halili shpk] was favoured”.

The Bank of Albania insisted it had followed the rules.

“The Bank of Albania is obliged to pay an invoice into the bank account indicated by the seller,” it told BIRN.

“The debts of the various subjects are a matter followed up according to the bailiff procedures through accounts in commercial banks.”

New governor, old issues

Financial stability is a sensitive issue in Albania, where the collapse of pyramid schemes in the 1990s wiped out savings and plunged the country into chaos.

Fullani’s term as governor was characterised – critics say – by lavish spending that often lacked transparency. Sejko was brought in ostensibly to steady the ship and restore the bank’s credibility.

Instead, the bank’s wage bill has soared 32 per cent over the past decade and other administrative expenses have grown six-fold.

In its 2017 report, the Supreme State Audit urged the bank to rewrite its regulations “immediately” and expressed particularly concern over its failure to move the conduct of procurement processes online.

The Bank of Albania objected to the preliminary audit report; parts were dropped in the final version, but the auditors stood by their conclusion that the purchase of the Hotel Dajti and other expenses were paid for with freshly-printed money.

The final report, however, was never published.

BIRN requested an official copy from the Supreme State Audit via a Freedom of Information request filed on July 24. The Supreme State Audit rejected the request five days later on the grounds that the report was confidential.

BIRN complained to Albania’s Freedom of Information Commissioner, who has yet to issue a verdict.

Soko questioned the grounds for keeping the report secret.

“It just shows the fear caused by the findings but also the fact that the new direction [being taken by the central bank] is hardly for the public good,” he said.