The bilateral agreement between Italy and Albania on irregular migration appears to be shaping a new model for addressing migration flows—one that could soon be mirrored by European Union member states under an emerging regulatory framework.

On Tuesday, March 11, the European Commission is set to present the so-called “Return Directive” in Strasbourg, a new legal framework aimed at accelerating the repatriation process for rejected asylum seekers. This regulation will serve as a foundation for all 27 EU member states, establishing common procedures for managing migration flows and expediting returns.

Among the 52 articles that constitute the new directive, there is growing speculation about a provision regarding the establishment of migrant reception centres in third countries. However, details remain uncertain. EU sources indicate that there is no official timeline for unveiling the new list of “safe third countries,” which will be compiled based on revised criteria. Unlike previous cases, the current EU legislation does not impose a deadline for the publication of this list, raising concerns about transparency and the feasibility of implementation.

Several EU member states—including Italy, Greece, Germany, and Austria—support the idea of setting up return centres outside EU borders as a deterrent against mass arrivals by land and sea, a crisis that has escalated significantly over the past decade. These countries argue that such measures could ease pressure on their asylum systems while discouraging irregular migration. However, the ethical and legal implications of such an approach remain contentious, with critics warning that this strategy risks shifting Europe’s humanitarian responsibilities onto non-EU nations.

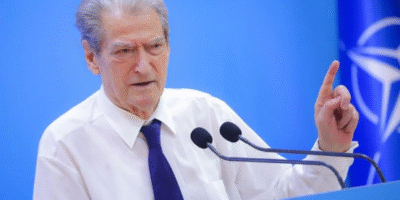

A similar model is already in place with the Gjader camp in Albania, established under the November 6, 2023, agreement between Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama. Under this plan, up to 36,000 migrants rescued by Italian authorities in the Mediterranean will be transferred to Albania, where their asylum applications will be processed.

While Italy hails this agreement as a pragmatic solution, concerns persist over the precedent it sets. Is this the beginning of a broader EU strategy to externalize asylum procedures, or does it represent an ad hoc arrangement with limited replicability? Furthermore, the agreement raises critical questions about the role of third countries in Europe’s migration governance: To what extent can they absorb the political, logistical, and social burdens of such policies?

As the EU moves toward formalizing its return policy, the Albania-Italy model may serve as both a case study and a test of Europe’s commitment to balancing border control with humanitarian obligations. Whether this approach will reinforce EU unity or deepen divisions remains to be seen. What is certain, however, is that the migration debate is entering a new phase—one where political pragmatism increasingly outweighs long-standing ethical considerations.

Written by our correspondent A.T.