TIRANA, Albania — On the day when Europe’s future was center stage in Albania’s capital, a protest staged just 400 meters away presented a striking contrast — not only in tone but in political trajectory. As leaders from across the continent gathered for the sixth European Political Community Summit in Tirana, Albania’s embattled opposition held a small but vocal demonstration, once again disputing the legitimacy of the country’s most recent elections. Led by former Prime Minister Sali Berisha — now facing legal troubles and mounting political isolation — the rally was less a show of strength and more a symbol of a deepening divide between Albania’s domestic political drama and its growing integration into European affairs.

A Tale of Two Events

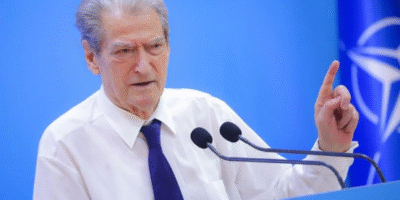

In the heart of Tirana, the summit served as a milestone for Albania’s European aspirations, with leaders reaffirming the country’s strategic importance in the Western Balkans. Prime Minister Edi Rama played host to European counterparts who praised Albania’s democratic progress, including the orderly conduct of the May 11 elections, which secured his Socialist Party a commanding majority in parliament. Yet just a short walk away, Berisha and a group of Democratic Party loyalists rallied under banners accusing Rama of electoral “massacre,” vote-buying, and collusion with criminal elements. While international observers acknowledged irregularities in some areas, they broadly affirmed the legitimacy of the elections — a conclusion starkly at odds with the opposition’s rhetoric. “The chair of Edi Rama rests upon the monstrous crime of stealing the vote of the Albanian people,” Berisha declared to supporters after returning from the International Democratic Union (IDU) summit in Brussels, where he claimed to have briefed global center-right leaders about the alleged abuses.

Political Theatre or Political Strategy?

The timing of the protest — coinciding with a high-level European summit — was no accident. Berisha, a seasoned political operator and former president, has long used moments of international visibility to amplify his grievances. But critics argue that such gestures increasingly appear disconnected from both public sentiment and international consensus. “This is less about policy or reform and more about survival,” said an EU diplomat in Tirana, speaking on condition of anonymity. “The opposition needs a narrative, and ‘stolen elections’ has become a recurring refrain — even when the facts don’t support it.” Indeed, the protest lacked a clear roadmap or tangible next steps. There were no new alliances announced no alternative program presented. What emerged instead was a familiar litany of accusations — including an attempt to frame even Albania’s successful bid to host a leg of the Giro d’Italia as a corrupt political ploy.

Opposition in Disarray

The Democratic Party, once Albania’s primary center-right force, is in disarray. Internal divisions, a loss of credibility among younger voters, and Berisha’s own legal entanglements (he is under U.S. and U.K. sanctions for alleged corruption) have weakened the party’s ability to offer a compelling alternative. In the May elections, the opposition lost 13 seats compared to 2021, and turnout among urban voters — traditionally a base for reformist politics — was notably low. Analysts say this reflects voter fatigue not just with the ruling party, but with an opposition perceived as more interested in grievance than governance. “It’s not that people are thrilled with Rama,” said Albanian political analyst Aulon Kalaja. “It’s that the alternative seems trapped in the past — a politics of slogans rather than solutions.”

Europe’s Balancing Act

For the European Union, Albania remains a critical partner in the Balkans — both for its geostrategic position and its relative political stability compared to neighbors. While Brussels has privately urged reforms in justice and governance, it has also recognized Albania’s progress, notably in judicial vetting and regional cooperation. But as Albania moves closer to opening full accession talks, the EU must walk a fine line — supporting institutional reform without appearing to dismiss legitimate concerns about democratic standards. “In any democracy, the opposition plays a crucial role,” said a European Commission spokesperson. “But that role must be constructive, grounded in facts, and aimed at institutional improvement — not merely delegitimization.”

As the summit wrapped up and European leaders departed, two narratives about Albania remained: one of promise and European alignment, the other of polarization and political stagnation. Berisha’s protest may have generated headlines, but whether it resonates with the broader public — or with Europe’s leaders — remains uncertain. What is increasingly clear, however, is that Albania stands at a crossroads. One path leads toward deeper integration and modernization; the other risks becoming mired in political theatrics and the recycling of old rivalries. For now, Europe seems to have chosen its preferred partner in Tirana. The question is whether Albania’s opposition will adapt — or continue to perform for an audience that is rapidly losing interest.

Written by our correspondent A.T.