In the shadows of Albania’s most recent elections, an old ghost has resurfaced—this time with a Balkan name and a notorious reputation: the Bulgarian Train. At first glance, it sounds almost folkloric. But behind the name lies a sophisticated, illegal mechanism of vote manipulation—one that, if proven true, undermines the very foundation of democratic participation.

The term Bulgarian Train refers to a classic electoral fraud technique known across parts of Eastern Europe. The process begins when just a single, genuine ballot paper—bearing the seal of the electoral commission—is smuggled out of a voting center. Once outside, the ballot is pre-filled by party operatives in favor of a preferred candidate.

Then, the cycle begins.

The marked ballot is handed to a voter, already complicit in the scheme. They enter the polling station and deposit the pre-filled ballot, but instead of using the blank ballot issued to them by the election commission, they hide it and smuggle it back outside. The fresh, unused ballot is then filled and passed to the next voter. The train keeps moving—ballot in, ballot out—until the station closes. The metaphor of a train is apt. Like an unrelenting engine, the scheme operates in a loop—each passenger (or voter) linked to the next, each action triggering the continuation of a calculated fraud. The method’s name, rooted in cases from Bulgaria and other parts of the region, evokes the murky transitions to democracy that still haunt post-communist states.

Ballot paper without a stamp in Peqin

The Democratic Party (PD) of Albania recently sounded the alarm, pointing to Peqin and Unit 9 in Tirana as possible sites where this ghostly train has passed. Yet so far, the accusations remain more shadow than substance. The Peqin case, in particular, lacks a crucial element: an authentic ballot issued by the Central Election Commission. Additionally, the very size of this year’s ballot papers—nearly one meter long—makes the notion of smuggling them undetected seem almost absurd. Can one hide a scroll of paper the size of a banner inside a jacket without notice?

According to opposition claims, a man named Dervish Beqiri was arrested after police seized ten allegedly forged blank ballots, a list of voters, and a sum of 280,000 ALL in cash. Also found were a hunting rifle and a sport pistol. He now faces charges of forgery and illegal possession of weapons. But whether this points to organized electoral fraud or merely personal recklessness remains unclear. So far, what the opposition has offered are not files, but metaphors.

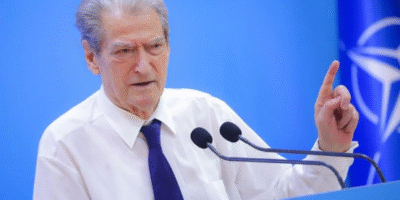

When former Prime Minister Sali Berisha promised evidence of the Bulgarian Train, he instead shifted the narrative toward “Elbasan vans”—another opaque term with little substance attached. Belind Këlliçi, a key figure from PD, claimed suspicions based on how ballots were folded—an irregularity that, while worth scrutiny, hardly amounts to a smoking gun.

Moreover, Albanian voting procedures include significant safeguards: ballots are serial-numbered, voter identity is electronically verified, and CCTV cameras monitor most polling stations. If the PD suspects fraud, the electoral code and constitution grant them the right to demand ballot box reviews and investigate the material evidence. In fact, they no longer need to protest or hunger-strike outside government buildings. The legal tools are in their hands.

Is the Bulgarian Train truly back? Or is it a spectre raised to stir political anxieties? The narrative—one part folklore, one part political theatre—could play well for an audience eager for dramatic explanations in the face of defeat. Yet Albania’s democracy deserves more than myth-making. If such a scheme indeed exists, it must be proven. Cameras, logs, serial numbers, and digital fingerprints all await scrutiny. The irony is that the very man who, in 2009, oversaw the destruction of electoral materials (thereby denying transparency to the opposition), now demands it. Times change, roles reverse, and perhaps that, too, is part of the train's circular motion. For now, the tracks remain unclear. But in Albanian politics—as in all political theaters—ghosts never disappear. They merely wait for a new stage.

Written by our correspondent A.T.