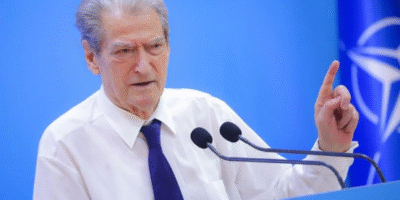

The recent Intergovernmental Conference in Luxembourg marked what Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama presented as another historic step toward EU accession. Flanked by Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski and Enlargement Commissioner Marta Kos, Rama seized the occasion to deliver a familiar script: Albania as a model candidate, the EU as a destination within reach, and the enlargement process as a matter of determination and reform. Yet beneath the carefully choreographed optimism lies a far more ambivalent reality – one where symbols obscure stagnation, and performative milestones mask the structural inertia gripping the EU accession process.

The opening of Cluster 2 (Internal Market) comprising nine chapters including free movement of goods, capital, services, and intellectual property, was officially celebrated as concrete progress. This follows the earlier opening of Cluster 1 (Fundamentals) and Cluster 6 (External Relations). Negotiating benchmarks have been set, and the European Commission reaffirmed its intention to monitor Albania’s alignment with the acquis. Yet, in practice, these openings remain procedural gestures within a rigid framework that rarely accelerates in response to candidate enthusiasm alone.

- “Today, we held the first Intergovernmental Conference under the Polish presidency. EU enlargement remains at the core of our priorities,”- declared Sikorski, invoking the familiar strategic language about the Western Balkans as vital to Europe’s security architecture.

While such language provides a veneer of momentum, it does little to mask the underlying contradictions that define today’s enlargement policy. On one side, candidate countries like Albania seek validation through symbolic inclusion – chapter openings, summit invitations, rhetorical praise. On the other, EU member states increasingly treat enlargement as a contingent possibility, subordinated to internal reform, institutional recalibration, and geopolitical risk management. In this context, Rama’s declaration, that Albania could open and close all chapters by 2027, appears less as a realistic projection and more as a discursive manoeuvre, calibrated for domestic consumption. The prime minister’s lyrical praise for Commissioner Kos, likening her to a “stopwatch” of enlargement, underscores how the Albanian narrative of progress often relies on personality-driven optimism rather than institutional traction.

But enlargement is not governed by sentiment—it is governed by structural logic. And that logic, increasingly, is one of delay.

This point is sharply articulated by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, which recently dismantled what it calls the “propaganda” of rapid accession. Journalist Michael Martens, citing Germany’s coalition agreement, underscores the central paradox of the EU’s enlargement position: while rhetorically supportive, the Union conditions future membership on internal reforms that themselves are politically elusive. Proposals like the abolition of unanimity in foreign policy decisions – seen as necessary for future enlargement – paradoxically require the very unanimity they seek to eliminate.

This institutional deadlock exposes the limits of the enlargement narrative in its current form. The EU may continue to open clusters, hold accession conferences, and praise partner countries for their progress. But without a viable roadmap for internal restructuring, enlargement remains aspirational. Berlin’s caution is not ideological; it is strategic. Enlarging without reform risks undermining the EU’s coherence, functionality, and geopolitical leverage. In that light, Albania’s accession trajectory cannot be divorced from the wider European context. The risk is not only that accession is postponed, but that the entire model of EU enlargement is undergoing transformation – from a merit-based progression to a deeply politicized calculus shaped by internal EU dynamics.

Moreover, there is a growing asymmetry between perceived progress and real influence. Albania may open clusters, but it remains structurally peripheral to EU decision-making. The Albanian government often celebrates technical steps – such as chapter openings – as irreversible, but these are reversible in practice. Compliance reviews, political crises, or shifts in EU priorities can stall or even freeze negotiations.

Meanwhile, the democratic fragilities within Albania – ranging from concerns over media freedom to judicial independence and electoral fairness – are treated as resolved or secondary in official discourse, even as they remain active obstacles to accession in the eyes of more sceptical member states.

At the same time, the EU’s own internal contradictions deepen. The possibility of future veto power being granted to countries like Serbia, whose geopolitical alignments are under increasing scrutiny, raises legitimate concerns about the governability of a larger EU. The calculus is no longer just about whether candidate countries meet the criteria, but whether their inclusion strengthens the Union as a whole.

This marks a fundamental shift in the philosophy of enlargement. The old logic, technical progress equals accession, is giving way to a post-functional logic, where even compliant candidates may wait indefinitely, pending broader political consensus within the EU. For Albania, this should be a moment of strategic reflection, not celebratory complacency. If enlargement is no longer purely procedural, then discursive realism, speaking honestly about the structural and political hurdles ahead, is more valuable than diplomatic choreography. The long-term credibility of Albania’s EU ambition depends not on how quickly chapters are opened, but on whether the country can build institutions that are resilient, independent, and genuinely democratic, even in the absence of near-term rewards.

In the end, Albania’s orbit around the EU will not translate into entry through rhetorical gravity alone. The path to membership is now less a linear roadmap and more a moving target, shaped by variables far beyond Tirana’s control. But one thing is certain: performing progress is no substitute for confronting the systemic impasse at the heart of EU enlargement.

Written by our correspondent A.T.