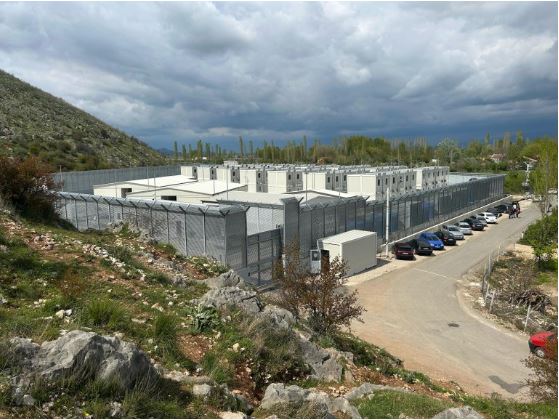

The newly established migrant center in Gjader, Lezha, created under the agreement between the Italian and Albanian governments, has returned to the spotlight following violent incidents that occurred on April 14. While the situation currently appears calm, the tensions inside the camp reveal the challenges and uncertainties of a model that remains controversial, not only operationally, but also legally and ethically.

The recent events, in which a group of about 10 migrants destroyed furniture and broke windows in their rooms, triggered immediate intervention by the Italian authorities managing the camp. The perpetrators were swiftly placed in isolation.

Although no official statement has been made, media reports and sources from within the camp shed light on a tense reality, where the clash between humanitarian expectations and security policies is increasingly evident.

Protests and acts of damage were also confirmed by sources from Italy’s Ministry of the Interior (Viminale), who reported that “a few windows were broken, but there was no riot,” emphasizing that the situation is now under control. The prison facility set up at the site, they clarified, has not been activated and currently houses no detainees.

From Temporary Shelter to Detention Center

Originally designed as a temporary reception center for asylum seekers rescued at sea, the Gjader facility has been transformed, under a new decree by the Italian government, into a detention center for migrants with expulsion orders. The maximum stay period has been extended to 18 months, a significant shift from the initial 28-day limit.

This transformation raises serious questions about the actual purpose of the facility: is Albania becoming a “buffer zone” for Italy’s internal migration issues? And if so, what guarantees are in place to ensure the protection of the fundamental rights of those detained?

The Migrant Profile and Management Challenges

The most recent group of 40 migrants, who arrived on the Libra vessel on April 8, represent a specific category, individuals denied asylum in Italy due to criminal records. This has justified, according to Italian authorities, stricter security measures and special procedural handling.

However, the aggressive behaviour exhibited by some, along with reports of self-harm, reveals a more complex context. It’s not only a matter of criminality but also of mental health issues, lack of legal aid, and psychological isolation.

The case of a 39-year-old Georgian man, who was returned to Italy after being deemed “unfit to live in a restricted community,” highlights gaps in the vulnerability assessment process, an evaluation that was overlooked for months in Italy but was finally conducted in Albania after intervention from his lawyer.

The Italy–Albania Agreement Under Scrutiny

According to Tavolo Asilo e Immigrazione (TAI), a network of organizations working on migrant rights, the agreement between Italy and Albania for the establishment of such centers constitutes a violation of basic human rights principles. Critics see it as an attempt to “export problems” and sidestep the responsibilities of the host state.

TAI has resumed its monitoring activities at the camp, alongside Italian and European opposition MPs, raising essential questions: Do migrants have guaranteed access to legal and medical assistance? Does the facility comply with the standards of the European Convention on Human Rights?

A Precedent That Sets New Standards?

The Gjader case is more than a matter of camp management. It is a precedent that tests the boundaries of national sovereignty, international law, and European solidarity. It provokes fundamental questions about Albania’s role in the EU’s migration mechanisms and about the ethics of accepting individuals with deportation orders under legally and humanely questionable conditions.

In this context, the recent unrest, though minimized by Italian authorities, is a symptom of a fragile structure. Without transparency, independent oversight, and sustained commitment to human rights, incidents like broken windows may signal deeper fractures in a system designed more for containment than care.

Written by our correspondent A.T.